By Narayan Srivastava

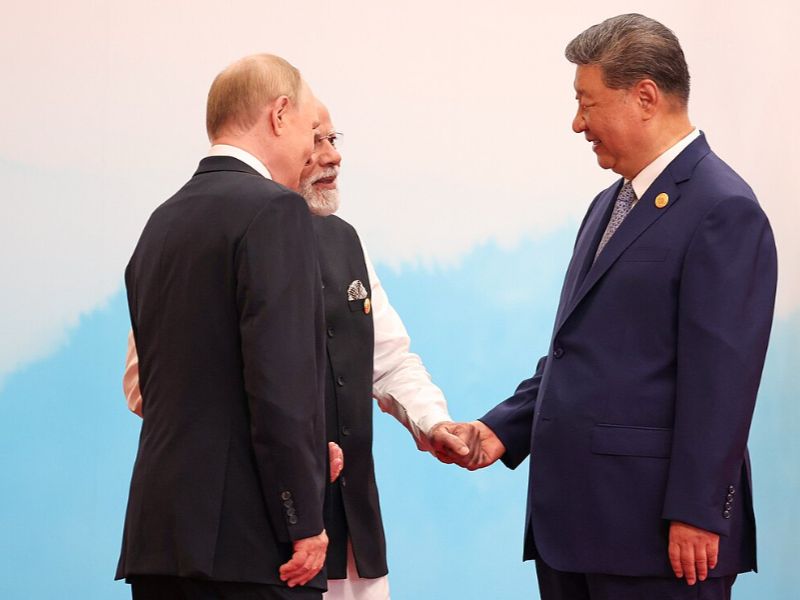

The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit in Tianjin which concluded this September put on display a tactical convergence among Moscow, Beijing and New Delhi that is less a formal alliance than a set of overlapping interests with tangible economic and military consequences. Vladimir Putin reaffirmed strategic ties with Asia, Narendra Modi balanced a show of reaffirmations of strategic autonomy with specific defense and economic discussions on the sidelines, and Xi Jinping used the platform to promote Sino centric initiatives and push a narrative of a “new global order.” As a result, the summit’s optics were political theater and transactional diplomacy, ignoring Russian violations of international law and even geopolitical interests that differ largely, particularly between Beijing and New Delhi.

Immediate, measurable losses for NATO-aligned interests begin with defence procurement and industrial competition. Russia publicly proposed joint production and technology transfer of its Su-57 fifth-generation fighter to India. If India were to accept the offer, it would shrink the market for advanced Western fighter jets and weaken the incentives for countries to remain tied to NATO-standard equipment and interoperability. This is specially concerning as India, the largest arms importer in the world, has relied on Russia for decades as its primary source of weaponry, and its military force includes Russian fighter jets. India’s $5.4–$5.5 billion S-400 air defense agreement, which was inked in 2018 is next to that offer. On the diplomatic sidelines, Moscow has hinted at more S-400 system deliveries and discussions. However, the conflict in Ukraine hindered Moscow’s export capabilities in recent years, forcing New Delhi to turn west. The summit thus has the potential to reverse South Asian defence market from going west as discussions on lucrative Russian offers take place.

These defense deals have real economic consequences for NATO countries. Since India is one of the biggest weapons buyers in the world, every move it makes toward Russian equipment or joint production with Moscow means a fall in business opportunities for Western defence firms. Beyond the financial hit, such choices also make it harder to build common standards in training that allow for interoperability and serve as the foundation of a long-term political alignment.

However, the effects on the economy extend beyond missiles, aircraft, and tanks. The second and more significant category of losses is trade and energy flows. In 2024, trade between China and Russia reached record highs of between $240–$245 billion, indicating Moscow’s ability to shift sanctions-affected trade and lessen the impact of Western economic sanctions that have been in place since 2014. Due to reduced spot oil prices, India’s trade with Russia also increased, reaching an estimated $65–$68 billion in 2023–2024. This served as Moscow’s financial lifeline, which is in opposition to the West’s policy of market isolation as Reliance, headed by Mukesh Ambani (India’s richest man), bought 33 billion dollars’ worth of crude oil from Russia since 2022. These trade movements alter diplomatic negotiations and make international law infractions seem acceptable despite worldwide condemnation, which is problematic for the current international order that relies on collective sanctions or market isolation to influence states to follow international law.

Third, the summit highlighted how control over chokepoints and supply routes has become vital and important for Euro-Atlantic prosperity. SCO leaders pledged to strengthen economic cooperation across Eurasia. This move, when combined with China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Russia’s entrenched energy networks, enhances the ability of non-NATO actors like China and Russia to shape global flows of energy, critical minerals, and manufactured goods. This is not an abstract risk geopolitical uncertainties outside NATO borders have an impact on NATO economies as well. According to UNCTAD, more than 80% of world trade by volume is carried by sea, and recent disruptions in the Red Sea driven by Houthi militant attacks on commercial vessels, including tankers and container ships linked to Western and allied nations have forced vessels to reroute around the Cape of Good Hope, increasing average shipping distances by up to 30% and raising freight costs significantly. Reuters reporting has further underlined that these delays and higher costs are already feeding into inflationary pressures in Europe and North America, raising the prices of fuel, food, and consumer goods. For Canada and other NATO members, whose economies depend on stable access to energy markets and critical minerals such as nickel, cobalt, and rare earths, these dynamics translate directly into higher costs for households and industries. In short, SCO diplomacy creates ripple effects that extend well beyond its geography, transmitting economic fluctuations into NATO economies in real time.

On the psychological and diplomatic level, Modi’s on-camera cordiality with Xi and Putin was what many consider a signal of India’s foreign strategy of geopolitical ambiguity which seems to oscillate between the west and Russia. Yet, Modi’s warmth toward Moscow is particularly striking and concerning because it comes from the world’s largest democracy with structural contrast to the authoritarian partners of the SCO summit and raises the uncomfortable question of whether this alignment is driven less by genuine convergence and more by a shared impulse to counterbalance the West, a dynamic NATO cannot afford to overlook. For NATO policymakers, that body language is a signal that India prefers transactional hedging to bloc membership. This complicates alignment but creates space for portfolio diplomacy.

Hence, converting partnerships into industrial and capacity offers is more critical now. Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy and its new investments show Ottawa is willing to invest in regional infrastructure and offers a diplomatic template for NATO nations to follow. Ottawa can push within NATO for a pooled offer that is attractive to non-aligned nations like access to Western markets and standards in return for closer interoperability on practical security issues.

NATO should expand naval coordination with willing Global South partners to secure chokepoints, escort commercial traffic, and provide assurance operations that reduce the incentive for buyers. This is not membership expansion, but it is operational diplomacy that protects trade and proves the utility of cooperating with NATO-aligned navies.

Finally, the Alliance must invest in political patience. India, which has now shown intact decision autonomy is more likely to respond to offers that combine lesser structural commitments with tangible benefits. The summit made clear India’s possibility of being ‘courted’ by transactional diplomacy. Modi’s posture at Tianjin was negotiable and sovereign, something which NATO can mirror to gain access to Into-Pacific geopolitics.

From a Canadian vantage-point Ottawa has both leverage and interests. Canada’s trade with India has been growing (US$8–9 billion in recent years) and its Into-Pacific Strategy channels nearly CAD$2.3 billion over five years for regional initiatives. These are levers Ottawa can use inside NATO to propose pooled Canadian-led offers on capacity building, green energy, and critical minerals processing that reduce the appeal of Russian or Chinese offers. Canada should press for NATO to use its cooperative security pillar to operationalize those offers.

The SCO summit showcased a pragmatic convergence among Moscow, Beijing and New Delhi to be a convergence of convenience, not an ideological bloc. This nuance matters the most for NATO as it does not need to become a global alliance to respond but needs a networked posture through practical, calculated partnerships, industrial scale offers, maritime assurance, economic alternatives, and quiet, effective diplomacy that speaks to the priorities of sovereign Global South nations. That posture preserves NATO’s Atlantic core while giving it the global purchase required to defend the rules-based international order.

For Canada, that means leaning into the Indo-Pacific Strategy with an approach that wins influence without diluting identity. The SCO handshake is a reminder that diplomacy is ever changing. NATO must treat it as such and defend what can be defended, partner where it matters, and invest where influence is won through tangible returns, not rhetoric.

President of Russia Vladimir Putin, Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi and General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party Xi Jinping, at the 2025 Shanghai Cooperation Summit in Tianjin, China. This image is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. (attribute www.kremlin.ru) Accessed via Wikipedia Commons

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada