Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney’s special address to the World Economic Forum (WEF) at Davos 2026 was Canada’s ‘canary in the coalmine’ moment. In an erudite address to foreign luminaries of industry and global finance, who had gathered in the shadow of President Trump’s annexationist desires for Greenland, the Canadian PM heralded a new global epoch of ‘rupture’ in the rules-based international order. He argued that middle powers, like Canada, must form new coalitions organized around legitimate norms, integrity, and principled rules to counter the power of economic coercion by great powers, thereby building new resilience networks of cooperation and order. No less than 24 hours after Carney’s speech, the President of the United States stood before the same audience and announced that Canada should be grateful to the U.S, also suggesting that he may impose 100% tariffs on Canadian goods if Canada finalizes a trade deal with China. In the ‘Donroe Doctrine’, the weak must indeed suffer what they must.

What does it mean for Canada to pursue a new order-building project in a world where the great powers of our time, the United States and China, massively outweigh all other nations in terms of gross domestic product, market capitalization by home corporations, and purchasing power parity (PPP)? In terms of network power, which is the potential influence exerted through inclusion, coordination, and control within networks, China and the United States are extreme power holders. A ‘counter-power’ system will have to negotiate within and outside of these existing economic, informational, and cultural networks. This will require mixed systems that build strength by creating multiple points of production and ‘purchase’ of ‘goods’ to de-risk against coercion.

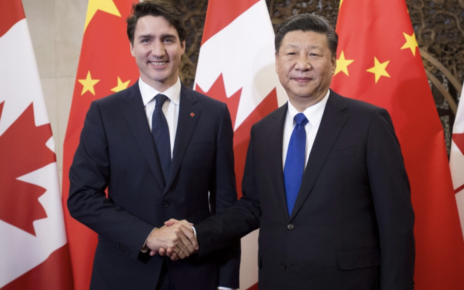

The effort will be global, but the Indo-Pacific should be of particular focus for strategic planners in Ottawa. The region’s economic dynamism is being fuelled by aggregate population growth and commensurate demand for goods and services. Much of this demand growth is, of course, driven by China, which is also Canada’s second-largest merchandise trading partner, with total two-way trade totalling CAD$118.9 billion in 2024. Carney’s recent visit to Beijing, the first by a Canadian PM since 2017, resulted in the outlining of a new strategic partnership promising cooperation on energy, climate, and renewed macroeconomic engagement. The visit and subsequent agreement with China signal a stabilization of relations between Beijing and Ottawa; however, they do not move the dial on dependence on great powers for purchasing Canadian goods.

To develop an effective and resilient model of ‘counter-power’, Canada will need to engage more deeply and broadly across the Indo-Pacific, focusing on leveraging collective capacity that can not only absorb costs imposed by great powers, but also retain the ability to impose true costs in response. For the former, this could include collaboration on critical mineral reserves and other essential inputs to emerging industries and military platforms. Australia is currently investing AUD$1.2 billion into developing a ‘Critical Minerals Strategic Reserve’, which secures the Commonwealth’s rights to minerals produced in Australia, including antimony, gallium, and rare earth minerals. Canada and Australia could collaborate to develop joint stockpiles of essential reserves, leveraging their combined endowment of rich deposits and established upstream exploration and production capabilities. This would also operationalize elements of the recently signed Joint Declaration of Intent Between Canada and Australia on Critical Minerals Collaboration, creating a new network supply node between the two democratically aligned middle-powers.

However, cost absorption can serve as an antecedent of network resilience only when the capacity to retaliate against coercion is credible. The current American administration’s unilateralism is based on the belief that the international legal system, as it exists, is a non-existent constraint on U.S. interests. For a ‘counter-power’ system to resist the Hobbesian impulses of a coercive power, it must have legitimate constraints that impose restrictions, and if necessary, penalties. This may look like the European Union’s (EU) anti-coercion instrument (ACI), which authorizes a wide variety of options across trade, investment, services, and financial markets and can also include restrictions on access to the single bloc market. Canada could help lead the development and potential harmonization of similar ACI measures across other global economies, creating a stronger cost deterrent that will allow countries to negotiate and respond from a position of collective strength.

Although described as a ‘counter-power’ network, the processes described here do not imply a severance from the United States or even China. Both nations are, in their own ways, strategically and economically vital to the current global economic system; it is impossible to build a new order without US$50 trillion of the world’s total GDP. There is also an undeniable indispensability of American military support to countries like Canada and Australia, which both rely on interoperability with U.S. command and control platforms and access to U.S. military technology.

However, indispensability does not equal kingship. Middle powers will not survive a world of Hobbesian anarchy and ‘self-help’ power politics. Without collective strength and modularity, powers lesser than those with the greatest military and economic might in human history will have little to no agency in a world carved into spheres of influence. Power will be consolidated in only a few central nodes that command the flow of global goods, entrenching resource dividends and consolidating capital.

Prime Minister Carney spoke against becoming a world of fortresses to conclude his 2026 WEF speech. In a world ruptured and fractured, the temptation may be to build high walls and long moats, particularly when the assaults are coming from your neighbour next door. The challenge for middle powers will be to confront a changed strategic landscape, and to understand where to build capacity and where to de-risk.

Photo Credit: Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs / Martijn Beekman. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution. Link here:

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.