China’s growing alignment with Russia is among the most consequential developments shaping the international security landscape. For NATO, understanding what drives this relationship is not merely analytical but strategic. Misreading Beijing’s motivations risks policies that could bind the two powers more tightly and deepen global divisions. China will remain a central actor throughout this century, and NATO’s ability to navigate its relationship with Beijing may determine the balance of power well beyond the transatlantic space.

A precise grasp of Beijing’s calculus is indispensable for NATO’s long-term planning. China’s partnership with Russia poses an indirect but serious challenge: Beijing provides Moscow critical economic and diplomatic support, helping Russia blunt sanctions and avoid isolation. Yet, their strategic motivations diverge sharply. While Russia seeks to overturn the post-Cold War order symbolizing its decline, China aims to rise within it. Beijing wishes to reform – not destroy – the institutional architecture that enabled its ascent.

This distinction is critical. Treating China and Russia as a single, cohesive bloc risks miscalculation. Their relationship is one of expedience, born of fear and reactive calculation, not ideological affinity. Decoding that logic offers NATO an opportunity to separate their strategic purposes and prevent a durable anti-Western coalition from solidifying. China’s rise came not through defiance of the international system but through integration within it. From joining the World Trade Organization to adopting global development norms, Beijing built its power on interdependence, prospering in an order largely designed by the West – an irony highlighting its divergence from Russia.

However, as China’s power grew, so did its sense of encirclement. This anxiety dates to the mid-1990s, when the Third Taiwan Strait Crisis exposed American military superiority. The dispatch of US carrier groups shocked Beijing, spurring modernization to ensure it would never again be so vulnerable. Subsequent alliance expansion – Japan’s remilitarization, new US bases in the Philippines, AUKUS, and the Quad – reinforced a narrative of containment.

What began as cooperation morphed into suspicion. NATO’s growing attention to the Indo-Pacific, though not aggressive in intent, has fed this siege mentality. Chinese leaders increasingly frame Western coalition-building as encirclement. Under such conditions, Moscow – despite its volatility – offers Beijing strategic depth: energy, a secure northern flank, and a partner vociferously opposed to US primacy.

Even so, the two powers remain far from natural bedfellows. Their history is scarred by mistrust. Chinese historiography recalls the “unequal treaties” that ceded vast territories in the Russian Far East, and Chinese commentary regularly notes that Vladivostok was once part of imperial China. Meanwhile, Moscow has long maintained contingency plans for conflict with China in its eastern regions. These undercurrents belie the superficial warmth of the alleged “no-limits” partnership.

Strategically, their aims diverge. Russia defines power through disruption; China defines it through endurance. Beijing prizes stability as the foundation for growth, while Moscow thrives in crisis. China still depends on global markets, Western technology, and stable trade routes. It cannot afford a collapse of the international economy – something Putin’s adventurism continually risks. Their regional behaviour differs as well. Since the Soviet collapse, Russia has continually interfered with and invaded its neighbours; China, by contrast, has not waged a war since 1979. These contrasting postures reveal that their differences are not merely rhetorical but embedded in statecraft.

These differences impose structural limits. China has avoided direct military support for Russia’s war in Ukraine, wary of sweeping secondary sanctions and reputational damage. Its backing has been diplomatic and economic, calibrated to preserve Moscow as a counterweight but not as a liability. Nor are its economic ties altruistic: Beijing exploits Moscow’s isolation to secure dominance over the Russian economy – a reality that unsettles the Kremlin. The Sino-Russian relationship is thus a marriage of convenience forged under pressure, sustained by perceived necessity, and haunted by unease.

For NATO, the challenge is to weaken this alignment without confirming the fears in Beijing that sustain it. The Alliance must resist viewing China and Russia as indistinguishable adversaries; doing so risks binding them further together. NATO’s approach must rest on clarity and finesse: recognizing China’s insecurities, offering alternatives to partnership with Russia, and maintaining dialogue that prevents misperception from hardening into enmity.

First, NATO must reassure China of its intentions in the Indo-Pacific and beyond. Beijing’s partnership with Moscow is reactive; the more it feels encircled, the more it leans on Russia. NATO’s cooperation with Indo-Pacific partners must therefore be framed not as containment but as stabilization. Declaring China an outright adversary would only entrench the internal narrative of Western hostility. Differentiating NATO’s Russia policy (focused on deterrence) from its China policy (centred on managed competition and selective cooperation) is essential.

Secondly, NATO should engage China where interests overlap. Beijing’s global ambitions are not inherently incompatible with Western ones. On issues including climate change, maritime governance, and counterpiracy, both share stakes. Cooperative mechanisms in these domains could serve as pragmatic confidence-building tools.

A key arena of convergence is Central Asia. Long under Russia’s influence, the region is pivoting toward a multi-vector foreign policy seeking diversification and autonomy. For China, Central Asia is vital as the corridor through which energy, trade, and investment flow westward. Yet, Beijing’s presence there has bred unease among local elites eager to maintain neutrality. This offers NATO an opportunity. By supporting transparent investment and resilient infrastructure, NATO members – especially EU states and Turkey – can foster stability that aligns with China’s economic interests while diminishing Russia’s grip. Central Asia thus becomes both a geopolitical hinge and a proving ground for how cooperation with the West, rather than partnership with Russia, can sustain prosperity.

Engagement, however, must come with firm boundaries. Beijing should understand that overt military or logistical support to Russia would incur serious costs. Quiet, consistent communication – avoiding public ultimatums – can make these red lines credible without humiliation. So far this approach has worked: Beijing has refrained from supplying lethal aid while maintaining official neutrality. NATO should continue this dual strategy of deterrence and discretion, ensuring China sees both the risks of deeper alignment and the rewards of restraint.

Importantly, NATO should emphasize that Russia’s recklessness harms China’s own strategic interests. Putin’s aggression has disrupted markets, driven Europe closer to the US, and accelerated decoupling trends that threaten Chinese exports. The message need not be confrontational but factual: Russia’s instability undermines the equilibrium China depends on. Reinforcing this perception can encourage Beijing to distance itself from the Kremlin.

History offers perspective. In the 1970s, deft American diplomacy exploited the Sino-Soviet split to reshape the global chessboard. Conditions differ today, but the principle endures: power lies not only in strength but in the ability to divide alignments through careful and pragmatic statecraft. China’s partnership with Russia is brittle, transactional, and constrained by mistrust. NATO’s task is to keep it that way.

The Alliance must pair firmness with restraint by deterring aggression while avoiding rhetoric that unites its rivals. It must engage China where interests converge while signaling that alignment with Russia is self-defeating. Above all, NATO must remain clear-eyed: Beijing is not Moscow. Its ambitions are reformist, not revisionist; its worldview competitive, not chaotic.

If NATO can act with patience and precision – understanding the logic that drives China while offering pathways that make cooperation more appealing than confrontation – it can forestall the emergence of a cohesive anti-Western bloc. Success will depend not on isolating China but on giving it reason to keep its distance from Russia. The stakes could hardly be higher. In managing the geometry of this twenty-first-century power triangle, NATO’s strategic dexterity will determine whether the coming decades are defined by confrontation or by a balance that limits conflict.

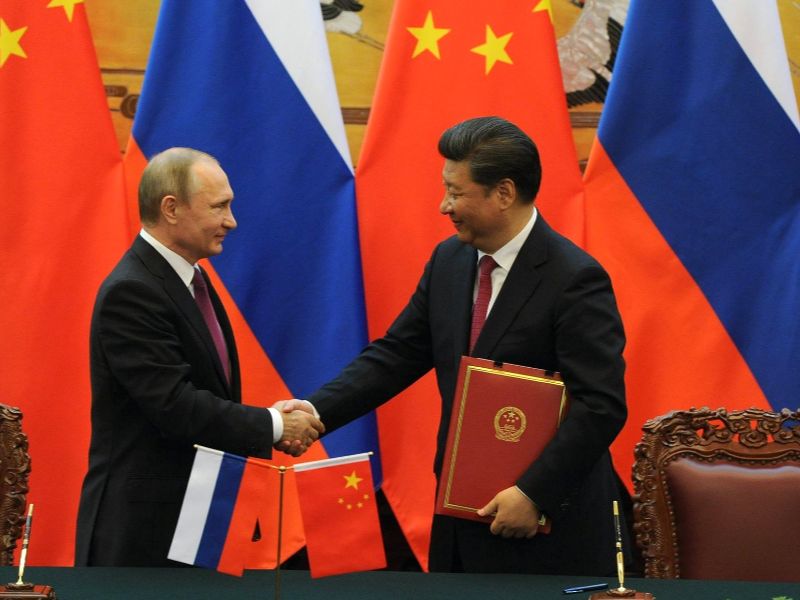

Photo Source: Russian Presidential Press and Information Office, www.kremlin.ru

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.