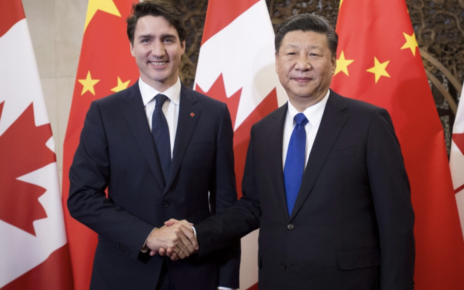

India has caught the attention of the international community with its newfound contentiousness in diplomatic relations with its partners. As recently as last month, New Delhi has clashed with not only its traditional democratic partners, Canada and the UK, but has also gone on the rhetorical offensive against Russia at last month’s Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit. At this same event, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping encountered one another for the first time in two years, and the iciness between the two could not be overlooked. India’s recent clashes with its various partners suggest a shift in its foreign policy toward a stronger strategic autonomy, enabling it to pursue its national interests while being less concerned about antagonizing other states.

Normally India has a good rapport with Canada and the UK, but that relationship has been tested following a recent referendum held by the Sikh diaspora in these two countries who voted to create a new sovereign Sikh nation, Khalistan. Furious at what the Indian government perceives to be foreign meddling in its domestic affairs, New Delhi drafted travel advisories discouraging Indian citizens from travelling to Canada and the UK for fear of “a sharp increase in hate crimes and anti-India activity.” In response, Canada issued its own travel advisories against India, causing a diplomatic row that has no end in sight at the time of writing. Clearly India is not concerned about antagonizing Canada.

Prime Minister Modi has also publicly demonstrated India’s strategic autonomy during the SCO summit. The summit was meant to be a moment of coming together with Russian President Vladimir Putin. Instead, Putin met a less than welcoming reception from his Indian counterpart. Having been made to wait for over an hour, Putin sat and listened to a chiding speech made by Prime Minister Modi at their bilateral meeting. During their public joint press conference that followed, Modi argued that the Ukraine War was hurting emerging economies by increasing concerns about food and security and the availability of fertilizers. He then publicly lectured Putin and said, “we must find some way out and you too must contribute to that.” Finally, and perhaps most pointedly, Prime Minister Modi concluded by exclaiming that “today’s era is not of war.”

If the Russian President thought he was going to receive tacit approval if not understanding for his actions, he did not get it from India. India was demonstrating its strategic autonomy in front of the whole world.

The rebuke of Putin is even more striking given India’s and Russia’s long history of mutual support. Ever since the early days of the Cold War, the Soviet-Indian relationship was based on three pillars: arms sales, a public sector-driven economy, and the Soviet-Indo bloc versus the US, Pakistan, and China. Although India was “non-aligned” in its foreign policy, it was clearly closer to the Soviet bloc than that of western countries led by the US.

As things stand today arms sales is the only remaining pillar of the Soviet-Indian (now Russian-Indian) relationship. With respect to the public sector economy, India no longer admires the Russian model. With respect to foreign alliances, New Delhi has allied itself with Russia in some instances (for example, when it abstained from joining the West’s sanctions regime after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine), but has also reached beyond its relationship with Russia to join alliances such as the QUAD, an organization “composed of India, Japan, the US and Australia and that promotes cooperation and dialogue among its members.”

Of all the diplomatic rows India finds itself in today, by far the most dangerous is the one with China. Their dispute has its origins in the 1960s, when India and China fought a war and China then annexed 15,000 square miles of Indian territory (nearly the size of the Province of Nova Scotia) in the Ladakh region. This Indian territory remains under Chinese occupation to this day. The wounds of the old war were re-opened two years ago in the Gawlan Valley Incident, when China tried to annex more territory and 25 Indian soldiers died. This represents a dangerous escalation of tensions in a region bordered by three nuclear-armed powers: India, Pakistan, and China.

This dispute is unlikely to be resolved in the near term as one of China’s main foreign policy objectives is to “regain territory lost over previous generations.” In 2018, President Xi Jinping told then-US Defense Secretary James Mattis “We cannot lose even one inch of territory left behind by our ancestors.”

India’s response has been to shift closer to its western allies. For example, at the September 2022 meeting of the International Atomic Energy Association, (IAEA) India provocatively lent its full support to AUKUS, the West’s defense coalition to introduce nuclear submarines into Australia to contain China in the region.

India has historically prided itself as a nation that does not belong exclusively in one camp or another. Most recently, it appears to be asserting its strategic autonomy more forcibly. What distinguishes today’s disputes with Canada, the UK, Russia, and China from India’s traditional balancing of national interests and alliances is that India’s growing influence in the region allows New Delhi’s policy makers to pursue their national interests more forcefully, with less concern about antagonizing other states.

Photo: “Shanghai Cooperation Organization in Samarkand, Uzbekistan 2022” (16 September 2022) by the Press Service of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan via<https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0> Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.