With the fight for Raqqa, the de facto capital of ISIS in full force, the future of Syria is being decided right now. At the end of this bloody civil war, perhaps, the only thing that is for certain is that Syria will have a long road to recovery. What began as an uprising against a dictatorship government during the Arab Spring, has metamorphosed into a full blown conflict between multiple self-interested armed factions within the Syrian region. What complicates the war further is the entry of different countries near and far who have joined either because they felt compelled to act out of their own national security interests or because of their own underlying strategic and territorial motives, or both. One such actor is Russia, having entered the Middle East in response to a formal invitation to intervene by the Assad government. Today, we see that Russia’s contribution has been the game changer in the war. By coming to the military aid of the Syrian government, Russia has managed to alter the fabric of Middle Eastern security and arrived as a force to be reckoned with.

Syria and Russia have enjoyed a strong bilateral relationship that goes back to the Soviet era. Syria was guaranteed independence in an agreement by Russia in 1946, as the ruling French government evacuated its troops. President Hafez al-Assad, the predecessor and father of current President Bashar Al-Assad, signed a treaty in 1971, allowing the Soviet Union to have a naval base in Tartus, Syria. The relationship was further cemented in 1980 with the signing of a Cooperation and Friendship Treaty. After the Soviet Union dissolved, Syria recognized Russia as its legal successor and inherited similar relations. In 2011, when Assad clamped down violently on pro-democracy protesters demanding his resignation, a UN Security Council resolution calling for sanctions from Western and Arab countries was vetoed by Russia along with China. Syria is also a major importer of Russian weapons, importing 78% of its arms from Russia as of 2012. Russia has always shown a sense of allegiance to Syria, its strongest ally in the Middle East.

In October 2015, it was reported that Assad formally requested Russia to intervene on its behalf in what was then, a losing side. Putin responded with military support for 6 months that bolstered Assad, after which he announced that the goal in helping the Syrian government had been ‘largely achieved’ and the process of withdrawal should make way for diplomatic efforts to begin a peace process. But what followed was different: as the situation on the ground continued to worsen, Russia renewed its efforts with heavy air campaigns against rebel forces. Internationally, criticism against Russia and the Syrian government grew, as did the massive scale of the resultant refugee crisis.

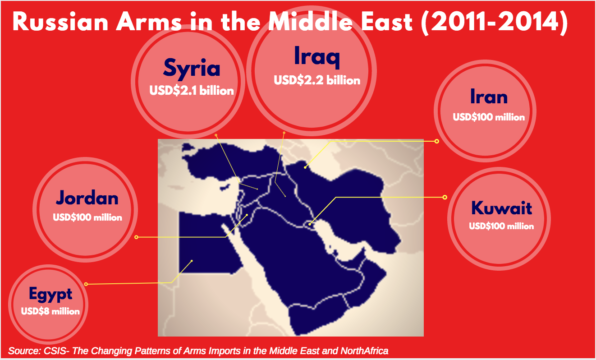

Russia gains from increased arms sales in the Middle East (see pictorial), after continually showcasing its weaponry in the Syrian civil war. The scale of Russia’s involvement in the Middle East can be attributed to the number of Russians fighting as jihadists in the Middle East. It is estimated that over 3000 Russians have left from the Russian and Central Asian region to fight in the Middle East. Russia fears that at some point, they might return home to cause havoc. The Russian government would rather fight these jihadists in the Middle East, as opposed to combating them on their own soil. The Chechen wars in the 90s demanding separatism were scalding for the government, and so it wants to contain the rise of religious extremism at its source.

Another aspect to the Russian presence in the Middle East comes from its distrust of the West’s capability of handling regime change of governments. This became apparent during the US Invasion of Iraq in 2003, which Russia did not support. Putin called the war a ‘political error’ stating that it was a breach of national sovereignty, while not condemning the reasons behind the invasion itself. Years later, the stance against the Western governments further hardened during the 2011 Arab Spring uprising, this time in Libya against the Gaddafi government. Gaddafi’s reaction was violent yet successful and so, spurred talks of a military intervention by the West. Russia initially warned against such a military action, citing that it would create room for religious extremism to rise, although later Russian leaders joined the Western powers to declare that Gaddafi ‘must go’. The civil war and the subsequent death of Gaddafi, resulted in chaos with Libya becoming a growing hotbed for terrorist activity that continues to destabilize the region. After the Libyan and Iraqi destabilization that Russia largely attributes to the West, it wants to makes sure that the Assad government doesn’t reach the same fate, because a future where Syria is taken over by terrorism spells serious security concerns for Russia.

Russia is strategically making itself a viable foreign power in the Middle East, especially as an option against the US . By supporting the Syrian government, Russia is sending a strong message to both its allies and rivals, even if it means irking the West. This was evident when Russia represented Syria in brokering two failed ceasefires earlier this year. Russia’s growing presence in the region is seen as it strengthens relations with Iran, and makes strides in Turkey in light of the weakening relations between US and Turkey. Furthermore, the wave of Russian arms flooding the Middle Eastern market shows that it plans to bolster its arms trade in exchange for allegiance. This behaviour seems quite similar to a historic US’ strategy during the World Wars and the years following.

Russia is now on the offensive and forming steady relationships with the nations that have fallen out of the US’ circle of friends. What is unexpected is the recent change in the political climate in the US, much to Putin’s satisfaction given his immediate positive response. Perhaps it is time to hope that the growing tensions between Russia and the West, especially over Syria, will dial down to a simmer–if only for the future of the world and the millions of people affected by the contention between these powerful nations of the world.

This article is the second part of Sha Lalapet’s series on Russia. To learn about the historical and economic workings behind Russia, please read The Dichotomy: Perception of Russia

The author thanks Neil Hauer, Aaron Korewa and Ian Litschko for their valuable insights that helped during the making of this article.

Photo: Putin welcomes Assad in The Kremlin, Moscow to discuss their cooperation in the Syrian war (2015), via President of Russia website. Licensed under CC BY 4.0. No changes were made to the image.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.