In 1954, China and India signed the Panchsheel Agreement in which they outlined five principles to govern relations between their states, since referred to as the “Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence”. The Five Principles include mutual respect for territorial integrity, nonaggression, reciprocal non-interference in internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence. These principles have become guidelines for not only China’s relationship with India regarding Tibet, but also for its wider foreign policy agenda. The principle of non-interference, in particular, has had an indelible impact on Beijing’s foreign policy behavior, much to the chagrin of some Western nations. In 2005, then U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick called on China to become a responsible stakeholder in the international system. There is still a strong sentiment in U.S. foreign policy circles that China’s global responsibilities have yet to catch up with its economic and political power.

Criticism of China’s non-interference policy has often focused on its dealings in Africa, a region where it has become the dominant foreign power both economically and politically. This dominance ensures China’s presence in almost all international political dealings on the continent, even when not physically present. When Hillary Clinton toured Africa in August of 2012, she drew attention to this issue by separating America’s involvement on the continent from other “powers” saying, “America will stand up for democracy and universal human rights even when it might be easier to look the other way and keep the resources flowing.” This was widely interpreted by many observers, including the Chinese, to be a slight against China’s activities on the continent. Ian Taylor, expert on China-Africa relations, notes on the other hand that with China’s outsized interests on the continent now, it will most likely be forced to abandon or at the least relax its non-interference policy.

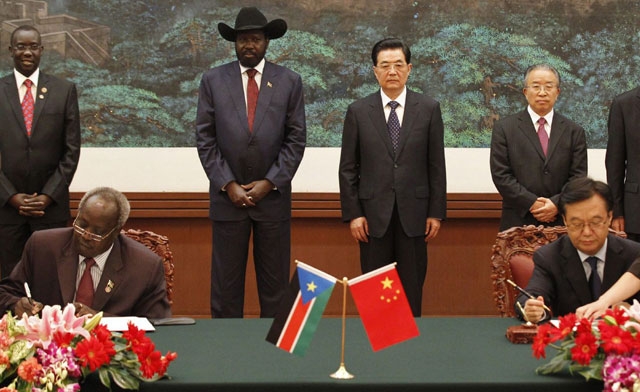

The best example of the tension that exists between protecting China’s interests in Africa, and its non-interference strategy is seen in Sudan, and now South Sudan. Before the secession of South Sudan, China invested almost $30 billion USD in Sudan, making China the country’s chief trading partner at a time when most countries implemented sanctions against Sudan because of the atrocities committed in Darfur. The relationship was at odds with China’s view of having a “peaceful rise to great power status”. In February 2007, then Chinese President Hu Jintao arrived in Sudan for a state visit. During the bilateral talks President Jintao expressed China’s deep concern over the Darfur crisis. Following the summit, China’s participation in the international talks on the Darfur issue were noticeably upgraded with Chinese officials playing a critical role in the U.N. plan for Darfur.

China is very pragmatic, and its leadership knows that an enhanced mediation role in resolving conflicts will bolster China’s credentials as being a “responsible power”.

It has been South Sudan that has really tested the Chinese commitment to non-interference. China is heavily invested in the young country, and is the largest foreign investor in the nation’s oil sector importing 70% of the South Sudan’s oil. After fighting broke out between South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir’s government troops and a rebel faction loyal to former Vice-President Riek Machar on 15 December 2013, China offered to mediate. Zhong Jianhua, Chinese special envoy to South Sudan, was sent to Ethiopia to help push talks between the two sides as well as ensure the safety of Chinese citizens and firms. More than 300 Chinese citizens had to be evacuated from South Sudan due to the conflict. The degree of Chinese involvement in the mediation process is deeply significant as it represents new territory for Chinese diplomats. In an interview with Reuters recently, Zhong acknowledged the significance of China’s participation saying “This is a challenge for China. This is something new for us … It is a new chapter for Chinese foreign affairs.”

Don’t expect China to take the lead on the negotiations or that this “new chapter” signifies an international activist China. Still sticking to the non-interference script while China feels out its mediator role, Zhong said “We are not the party to propose our own initiative, at least at this stage. So, we urge all parties concerned to respect an African solution proposed by African parties.” There’s more to this diplomatic foray then just securing China’s interest in South Sudan. China is very pragmatic, and its leadership knows that an enhanced mediation role in resolving conflicts will bolster China’s credentials as being a “responsible power”.

The important question to ask remains, is China’s engagement with Sudan the beginning of a new type of engagement with Africa, where it actively participates in the political affairs of other countries? More broadly, does this new foreign policy chapter mark the beginning of a more assertive China as its interests become even more entrenched in other regions of the world?