When Vladimir Mukhin, world-renowned Russian chef and owner of the 28th best restaurant in the world, White Rabbit, describes the food of his country’s still-recent Soviet era, his words are anything but glowing.

“I hate [Soviet cooking] because it totally killed Russian food,” remarks Mukhin. “Before, Russian food had colour. The Soviet period was grey. Everything was grey. Everyone was grey.” In a way, cuisine in the USSR can be taken as an example of and an allegory for life as a whole under the totalitarian regime. Engineered, political, public, and rigidly controlled, Soviet cooking served not just as a tool for nourishment but for state propaganda. Since the end of the Cold War, however, a nascent wave of “Russian” cuisine has slowly emerged, rediscovering pre-revolution traditions and marrying them with global techniques that developed outside of the USSR. Mukhin is at the head of this movement, and Russian chefs and diners alike have come to endorse the cultural growth made possible through Russia’s reintroduction into the global zeitgeist.

Unlike most of the world’s dining culture, that of the USSR was designed, quite literally, by committee. After the fall of the Imperial government, Soviet officials declared simultaneously that cooking food in the private home was an inefficient use of resources and that public cafeterias would free women from the “kitchen slavery” that made them unequal. The food of the revolution was a patented blend of ideological aspiration, harsh practicality, and political expediency.

“Old-fashioned Russian food was deemed ideologically inappropriate,” Russian food writer Anya von Bremsen elaborates, whereas the new Communist “traditions” presented recipes that incorporated food from across the Soviet Union, theoretically fed all citizens equally, and even more theoretically allow women to pursue culturally active lives when freed from the kitchen. These practices were codified in the “Book of Tasty and Healthy Food,” created by Stalin’s food commissar, Anastas Mikoyan. The recipes were to be implemented in Stolovayas, state-run cafeteries, as well as the communal kitchens shared by neighbours in the urban apartments that were provided to workers.

Whether or not the new culinary routines of the Soviet Union were convincing is debatable, but they undeniably served other, much more concrete purposes. For one, regimented cooking meant that the state could conserve resources and attempt to feed its citizens in the face of intense food shortages and economic isolation. Canned food became a staple of Soviet cooking, due to its cheapness and its ability to be industrially produced, and international produce was replaced by foods from within the USSR’s borders. The “Book of Tasty and Healthy Food” was propagandistic, presenting recipes of suckling pig and recommending four meals a day. But in a much more real sense, it was designed to provide instructions for meals that were resource efficient, if not always palatable. Furthermore, communal cooking and dining not only advanced an exclusively public meal culture, but in turn allowed for more rigid forms of totalitarian control. With private spaces eliminated, discourse instead occurred publically amongst neighbours and workers, where monitoring the spread of information would be much easier.

The fall of the Soviet bloc heralded with it an influx of Western culture, and before long Russia was filled with McDonald’s, Pepsi Cola, and Pizza Hut. With the rise of fast food and, in more upscale establishments, dishes from outside of Russia, Soviet dining faded out along with the regime that created it. While this for a time meant that Russian cuisine was nonexistent, it has over time returned to the fore. This is in part due to the efforts of chefs like Mukhin, who have endeavoured to rediscover the recipes and techniques that were suppressed under the USSR’s rule. Using past writings, intergenerational knowledge, as well as the new techniques introduced to Russia since 1992, a new, vibrant Russian food scene has emerged. Even Stolovayas have made a return, albeit in an ironically capitalistic way. Cafes likeStolovaya 57 offer cheap, canteen-style food that is predictable and to an extent nostalgic for those who lived their entire lives under the USSR.

Ultimately, a study of the Russian culinary scene demonstrates the cultural growth that can occur in the absence of totalitarian control, as well as the societal value linked with participating in the global order. The collapse of the Soviet Union allowed with it Russia’s introduction into the global food community, and perhaps even more importantly the rediscovery of its own past and traditions. While Soviet food programs served very specific purposes, they also stagnated the culinary, and in turn cultural, voices of the people within the USSR. While cultural totalitarianism may benefit the overarching regime, Russia demonstrates the progress that can come from a society that permits individuality and the spread of global knowledge.

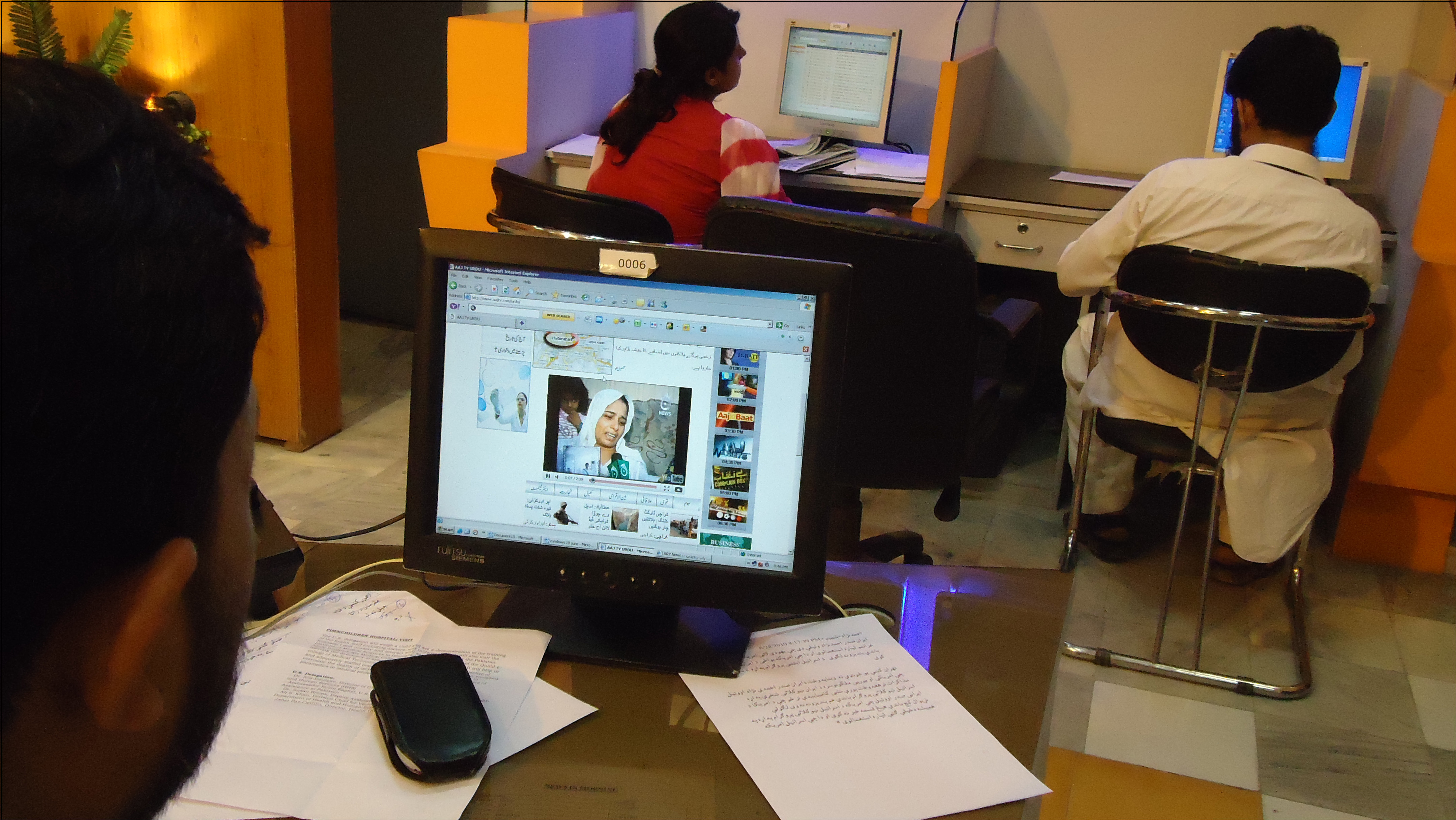

Photo: The Red Square GUM (Russia’s main department store chain) in which Stolovaya 57 and many establishments like it are hosted (2016), by Diego Delso via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.