Abstract: The Trump administration has slapped tariffs on numerous trading partners. On the surface, this has been used to overhaul outdated and imbalanced trade agreements which have not been in the best interests of the United States. President Trump, however, has been particularly aggressive toward the United States’ largest trading partner: China. Is the United States using tariffs to contain China’s economic aggression?

In accordance with President Trump’s economic policies, the administration sought to balance one-sided trade deals by slapping tariffs on several trading partners, including allies such as Canada and the European Union. To the avail of the United States, the U.S. economy is one of the most complex and diverse in the world, with no single trading partner holding a significant amount of influence. In other words, American exports are not concentrated to one specific destination. As a result, this insulates the United States economy from the substantial damage a single trading partner could inflict by using retaliatory tariffs. In some countries, however, a disproportional percentage of its exports travel to the United States. For example, 74% ($268bn USD) of Canada’s exports are sent to the United States.

Trade Deficits

A key motivation behind President Trump’s imposition of tariffs on a number of America’s trading partners is to reduce its trade deficits with these countries. The United States’ trade balance typically broke even until the mid 1970s. Since then, however, the US has been running significant trade deficits. Trade deficits occur when a country essentially spends more money than it makes, resulting in a current account deficit. The magnitude of the trade deficit depends on a multitude of factors such as the exchange rate of the dollar (a strong dollar means foreign goods are cheaper to buy), the growth rate of the US economy (increased growth allows a greater income for Americans to buy foreign goods) and the relative ease with which trade is allowed to flow between countries, such as though trade deals like NAFTA. Free trade deals provide manufacturing industries incentive to relocate outside U.S. borders where they are likely to find cheaper operating and labour costs, which then subsequently result in a dependency on foreign imports. In addition to such factors, the introduction of China to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 dramatically accelerated Chinese export growth, allowing an increased flow of Chinese imports into the US.

Simply put, trade deficits emerge when a country spends more money on its imports than it creates from its exports. For the first nine months of 2018, census figures show that the United States has imported roughly $1.8tn USD, while exporting only $1.2tn USD, and as a result the United States has run a deficit of more than $600bn USD. During this time, the E.U contributed roughly $120bn USD to the United States’ trade deficit, and Canada contributed $15bn USD. These figures, however, are minute in comparison to that of China, which surpassed Canada as the United States’ largest trading partner in 2015. China’s trade deficit with the United States is a staggering $301bn USD for the first nine months of 2018 alone. In fact, there are only a handful of economies that the United States holds a trade surplus with such as Hong Kong ($23.4bn USD), Netherlands ($19bn USD) and the United Arab Emirates ($9bn USD), for the first nine months of 2018.

According to the World Bank, 37% of China’s GDP in 2016 was based on trade surpluses of $1.04tn USD, of which 19% ($436bn USD) was attributed to trade with the United States. In the United States, however, only 26% of its GDP in 2016 was attributed to trade. As such, the Chinese economy is roughly three times more dependent on exports than the US, providing the US with a certain degree of insulation from a trade war. Roughly only 9.9% ($112bn USD) of China’s imports originate from the United States. As of June 2018, the Trump administration has introduced a 25% tariff on over 800 categories of Chinese imports, including steel, aluminum solar panels and washing machines, worth over $50bn USD.

Containing China

Moreover, besides simply balancing one-sided trade deals with trading partners, there are other motivations for the Trump administration’s swift actions against China. Many governments, including the United States, have expressed concerns about China’s “Made in China 2025:” a ten year initiative launched in 2015 which seeks to establish Chinese market dominance over several high-tech industries, including agricultural technology, aerospace engineering, bio-medical equipment, and high-end rail infrastructure, among others. Hi-tech products are generally assembled across many national boundaries, with highly specialised components often produced in a single country, capitalising on the essence of free markets. China aims to obtain 70% self sufficiency in hi-tech industries through subsidized domestic industries which would position China to dominate the global hi-tech supply.

Policy experts and security officials have outlined the threats to national security associated with China’s ambitions in acquiring control of entire industries. Furthermore, the methods by which China hopes to achieve this goal are troubling. A White House report in June 2018, alleged that China was taking advantage of open markets, including those of the United States, Australia and the European Union, to acquire intellectual property and key technological capabilities, both industrial and militaristic. Chinese strategies include the physical and cyber-enabled theft of technology and intellectual property, regulatory strategies, economic coercion, information harvesting, and state-sponsored foreign direct investment. The value of technology which China has come into possession of between 2007 and 2017, is estimated to be roughly $40bn USD.

In light of these allegations, open economies including the United States and the European Union, have begun taking steps to prevent China’s economic aggression by restricting access to their markets to Chinese investors, and demanding transparency. Governments have cited Beijing’s lack of protection for intellectual property as justification, and have accused Chinese government subsidies of having distorted the global economy. While American and European markets have been relatively open to China, this has not been reciprocated, as China’s markets have become increasingly restrictive to foreign investment.

China is a rising economic powerhouse, and experiences one of the fastest GDP growth rates in the world. Only 30 years ago, China had an estimated 750 million people living in abject poverty, although in 2015 that number has decreased to less than 1 million. As this trend continues, China could possibly eclipse the United States as the world’s largest economy, and perhaps challenge U.S. economic, political and military hegemony as the sole superpower. The trade tariffs the United States has imposed on various Chinese imports may act as a tool to prevent Beijing from obtaining unlimited access to the the largest economy in the world, and as a barrier to prevent further Chinese espionage. This could result in a more positive trade balance, and prevent China’s economic aggression against the United States.

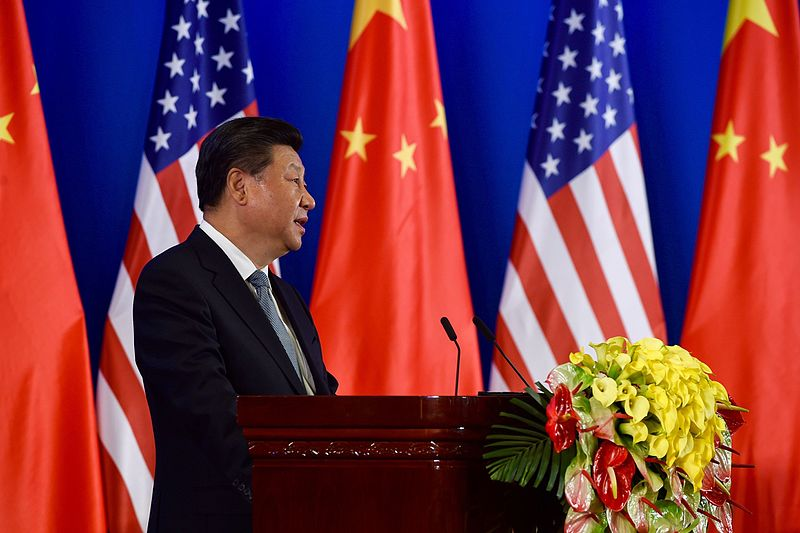

Featured photo: Chinese President Xi Addresses the Opening Session of the U.S.-China Strategic Dialogue in Beijing, (2016), by: U.S. Department of State via Wikimedia Commons. CC 2.0.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.